Margaret Pless (@Idlediletante) has posted a blog accusing Sargon of Akkad of “flabbergasting” copyright infringement. As the Witchfinder did his (4.5K word) GDL final coursework on internet copyright law (and passed), your author decided to analyse her claims. Her most recent article, “Specific Instances of Copyright Infringement by Sargon of Akkad – A Database Approach” is here.

[Disclaimer 22/08/2015] This article is meant as commentary on current events and should not be relied upon as legal advice.

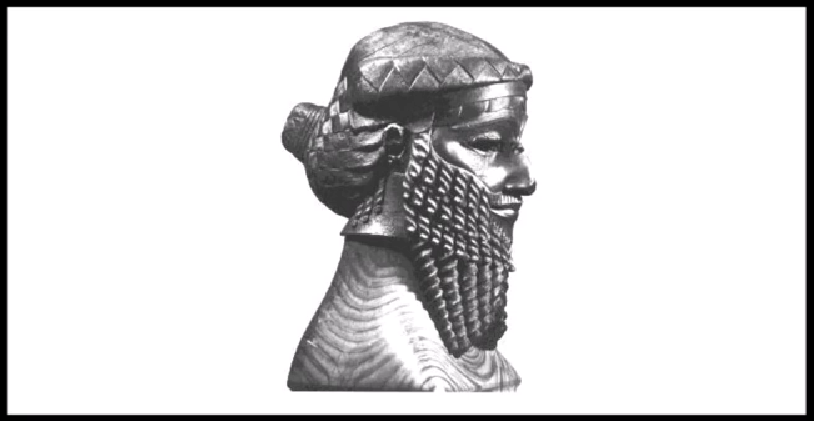

A one frame still from Sargon of Akkad’s 12 minute video, “Old Man Yells at #GamerGate” here – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WwsPai-0Ov8 , used to illustrate criticism or review pursuant to s30 Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Firstly, I do not want to be mean to Margaret Pless. I actually quite like her. She is a wildly overzealous leftist who often … goes a bit far – just like me at her age. However she is mistaken on her copyright law so I thought I would post this commentary on her recent article. I am secretly hoping that in the fullness of time move to the right. That process however, usually takes years.

In the meantime, I am going to analyse her most recent article –

“Sargon of Akkad is well known for his reliance on heavily sampling video from other sources to make his shows. The justification seems to be that because Sargon hasn’t sought permission to use these videos, his work must qualify as fair use“

Sorry. Basic legal error. ‘Fair Use’ does not exist in English law. Sargon lives in England. Both UK and US law give effect to the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, signed in 1886. However, they are not identical.

Whilst the UK does have a similar doctrine it is called ‘Fair Dealing’ and a little different because it pre-dates the UK equivalent of the 1st Amendment, Article 10 ECHR, which was incorporated into UK law in the Human Rights Act 1998 As it happens however, Sargon complies with ‘Fair Use’ too.

Fair Dealing

Let us go quickly through the statutory criteria for ‘fair dealing’ first, taken from the UK Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988 (I am using the current text, the legislation.gov website is slightly behind recent amendments at the time of writing, as it says) –

“30 Criticism, review[, quotation] and news reporting

(1) Fair dealing with a work for the purpose of criticism or review, of that or another work or of a performance of a work, does not infringe any copyright in the work provided that it is accompanied by a sufficient acknowledgement [(unless this would be impossible for reasons of practicality or otherwise)] [and provided that the work has been made available to the public]. […]”

So dealing with a work “does not infringe any copyright in the work provided” –

(a) it is for the purpose of criticism or review

These expressions are broadly construed by the UK Courts. In Pro Sieben Media A.G. v Carlton Television Ltd & Anor [1998] EWCA Civ 2001 the Court of Appeal approved a very broad approach. Lord Justice Robert Walker, said this –

“‘Criticism or review’ and ‘reporting current events’ are expressions of wide and indefinite scope […] They are expressions which should be interpreted liberally […]”

“[…] Criticism of a work need not be limited to criticism of style. It may also extend to the ideas to be found in a work and its social or moral implications. […]”

The other judges in the case, Lord Justice Nourse and Lord Justice Henry, concurred in that judgement.

(b) there is sufficient acknowledgement (unless this would be impossible for reasons of practicality or otherwise)

The meaning of ‘sufficient acknowledgement’ is defined at s178 of the Copyright Designs and Patent Act as –

““sufficient acknowledgement” means an acknowledgement identifying the work in question by its title or other description, and identifying the author unless—

(a) in the case of a published work, it is published anonymously;

(b) in the case of an unpublished work, it is not possible for a person to ascertain the identity of the author by reasonable inquiry;”

However, this will be interpreted reasonably by the Courts. On YouTube, for example, the common practice is to link the original, which will generally include the title, description and pen name of the author.

One video cited by Pless is here. Sargon uses extracts from a video by ‘Bad Preachers’ called, “Our Sign Says, “Male Leadership”. Pless states that it is not cited. This is incorrect. Sargon found the video on the Huffington Post, which clearly shows the title and author at 6 minutes 12 seconds. It says, “Bill Lytell: Our Sign Says, “Male Leadership””. It is unclear who took the video of Mr Lytell, whether ‘Bad Preachers’ took the video or whether they obtained it elsewhere. Their video description does not say.

I made ‘reasonable inquiries’ by way of several Google searches and could not find the copyright holder for the segment reproduced by the Preachers and so suggest it was ‘impossible for reasons of practicality or otherwise’ for Sargon to do so per s30(1) of the Act.

It appears Sargon made good faith efforts to cite. There is clearly no mens rea for any criminal copyright infringement. Even if his citation were technically deficient it is also unclear what (if any) actionable loss the copyright holder would seek to remedy. Perhaps notional damages for breach of their moral right (s77 Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988)?

(c) the work has been made available to the public

Self explanatory – Sargon generally only deals with public videos and articles.

(d) the dealing must be ‘fair’

This is defined by case law. The criteria for ‘fairness’ in this context were helpfully touched on by Mr Justice Mann in Fraser-Woodward Ltd v British Broadcasting Corporation Brighter Pictures Ltd [2005] EWHC 472 (Ch).

Pless says,

“An important consideration when evaluating a fair use defense is length of the video sampled. In 44 of the 95 videos studied (or 46% of the time), Sargon uploaded copyrighted video in its entirety”

Pless has a point – quantity is relevant. However the purpose of Copyright law is to allow the creator to profit from their work to allow the creative industries to be financially viable. The issue of quantity is allied to the key question of ‘competition’. Dealing is ‘unfair’ if it competes with the work. Pless encapsulates the point thus –

“It’s worth asking whether this sampling in toto would be considered fair use in any other medium. For example, if the New York Book Review published an entire novel with snarky marginalia written in red ink and called this a critique, would that constitute fair use of the author’s work? And if not, where does Sargon’s “criticism” stand?”

She has the essence of it. However, Sargon’s frequent approach is basically to take source material, chop it into numerous sections and intersperse it with prolix commentary. In short he is using it for bona fide criticism. The central issue is that I generally do not think he is competing.

I simply do not see hordes of Guardian readers forsaking their left wing sanctuaries to get free videos on Sargon’s channels whilst forwarding past his protracted commentary sections.

Even if there were a marginal few who were in fact taffing free left wing videos, commercial use for criticism allows some actual damage. Mr Justice Mann said this –

“64. How, then, does that affect the assessment as to the fairness of the dealing? Risk to the commercial value of the copyright may go towards demonstrating or creating unfairness, but it does not follow that any damage or any risk makes any use of the material unfair. If it did then there could be no use of copyright material in criticism or review if it could be said that that use might damage the value of the material to the copyright owner. […]”

Fair Use

The US doctrine of ‘Fair Use’ began in case law, but was codified in the Copyright Act of 1976. The ‘Fair Use’ section is at 17 U.S. Code § 107 and states –

“Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include—

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for non-profit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors.”

Again, reproduction for “[…] criticism, comment […]” is allowed. Fairness is to be determined by the Court and takes into account “the potential market for” the copyright work. The “heart” of the doctrine has been said to be whether the allegedly ‘fair’ use is ‘transformative’ to a new work or a taffing of the old. (I am obviously paraphrasing – the Supreme Court never said, “taffing”).

In Folsom v. Marsh, 9. F.Cas. 342 (C.C.D. Mass. 1841), regarded by some as the first United States Case on Fair Use, Justice Story ruled,

“[…] Thus, for example, no one can doubt that a reviewer may fairly cite largely from the original work, if his design be really and truly to use the passages for the purposes of fair and reasonable criticism. On the other hand, it is as clear, that if he thus cites the most important parts of the work, with a view, not to criticise, but to supersede the use of the original work, and substitute the review for it, such a use will be deemed in law a piracy […]”

In passing I also note that the US statute does not actually require acknowledgement.

Conclusion

In my opinion, Sargon’s work is both Fair Use and Fair Dealing. He is not aiming to usurp the market for his subjects but to engage in genuine comment illustrated by the lengthy extracts. For the same reasons I consider Pless to be mistaken.

Hi Sam –

Writing several years later to tell you how much I treasure this follow-up. Whether I am more right-leaning than I was two years ago remains to be seen, but I will concede that my article about Sargon’s copyright infringement likely addresses issues of the spirit of the fair use defense better than its legal specificity.